Scree (almost) goes on holiday to Scotland…

Since the start of the year, there’s no doubt. I’ve worked too hard! And my late June trip to Big Sands beach and campsite near Gairloch was looking like no exception. No matter how I tried to put a positive spin on things, spending 7 to 8 hours per day writing a funding bid wasn’t looking much like time-out. Yet having taken on too much as of late, not working would have undoubtedly been more stressful still. So there I was at 7am every morning: already at my picnic table desk having roused myself with a dip in the sea, putting in some early work hours to leave time for more familiar kinds of holiday adventure later on in the day. I’ve never really been one for lazy (aka relaxing) holidays, and my Scottish trips have long tended towards hill-running adventures, which on this occasion seemed to be increasingly focused on climbing Corbetts (those Scottish hills in the 2,500 to 2,999 feet height category below the Munros). I say this as if I was surprised, and I was really. At no point had I sat down and decided that the Corbetts were on my agenda. Rather, I was simply going out and climbing new hills, as was my wont. Going to new places. Doing something different. And certainly there was no ‘harm’ in getting out my blue Bic ballpoint at the end of the day and making a record of where I’ve been, and when. Right?

It’s a slippery muddy peak-bagging slope. Not even one week in, I found myself flicking through the guidebook to work out how many Corbetts I’d climbed already, how many were left to go, how long it would take me to finish bagging them, and (slightly strangely) what age I’d be by then! Good, I guess, to know that you’ll still be alive by the time of compleating them! Already on this holiday I’d done an epic late afternoon / evening run up Beinn an Eoin and Baosbheinn, and a fabulous scramble along the ridge of Beinn Dearg, the retiring, somewhat neglected mountain in the Torridon range. I’d given up even pretending to run the ridge between Sgurr nan Lochan Uaine and Sgurr Dubh it was so rough and pathless, and the quartzite scree slopes so endless. All of this squeezed around my priority task of writing a 15,000-word fundraising application for the poetry festival which I’d taken on the Directorship of alongside my work on Scree (which at this point had started to flag rather as a result of other workloads). Next up on the schedule were Meall a’Ghiuthais and Ruadh-stac Beag, and then I’d spend a three-day backpack ticking off four or five Corbetts in Letterewe Forest…and before I knew it?

Darn. Did this mean that Scree, and all of my ideas behind it, were broken? Corbett bagging? Really? Wasn’t Scree meant to be about getting away from a target-setting approach to the outdoors? Exploring other, less instrumental and more wandering approaches? What chance did the project stand if I couldn’t even stick by its principles for the duration of a single year? It was as bad as the time I turned vegan, wrote my (painfully idealistic) university dissertation about the philosophy of a meat-free diet, only to be broken within the year by a shiny wedge of Stilton which my parents had bought, during a holiday in the Outer Hebrides. By comparison, my week-old vegan fare had been looking rather mouldy (!!), and back in 1997, vegetarian supplies weren’t the easiest to come by in Harris.

Of course, my tendency to overcommit myself, and work too hard, comes from a not dissimilar high-achieving mindset to my peak-bagging one, which in is turn encouraged by the particularly target-driven culture that we live in. At the same time that I heard I’d been successful in my Arts Council funding bid for Scree, I was also appointed Director of StAnza, Scotland’s International Poetry Festival. Even on paper it was too much, but I simply wanted to do them both! How exciting! Of course I could manage! It would just be a busy year…! And let’s face it - I’m yet to meet the freelancer who doesn’t take on too much for fear of impending ‘famine’. Having turned freelance in February 2020, my own memories of the ‘famine’ involved in trying to live off Universal Credit during the Covid lockdown were far too recent. When did hard work kill anyone?

In fact, by the time I arrived in Gairloch, I wasn’t too far off finding out. I’d already started dreaming about bits of my head (literally) falling off because it was too full, and I was probably more exhausted than I’ve ever been. It wasn’t just workload - I was really struggling to contain the concepts and ideas behind two major, and very different, projects…In this context, I’m sure that you’ll be glad to hear that I didn’t climb Meall a’Ghiuthais and Ruadh-stac Beag. And I didn’t tick off the four or five Corbetts in Letterewe. No. The weather in the north west was turning, so I headed to the Cairngorms instead to ‘bag’ whatever I could find by way of Corbetts there! Running up to the top of a hill at 10pm to ‘bag’ an extra peak? No problem. It’s Scotland, in June, and light until pretty much forever. Of course, I told myself that I wanted to see the non-existent sunset.

However, the whole experience, in the context of Scree, did get me thinking. Just before I’d set off on my not-a-holiday, Summit (the British Mountaineering Council magazine) had published a three-page spread about the project. In response, a number of people had written to me, including a fella who wanted to tell me all about his Not-quite-there club. With a burgeoning membership of one (himself), the aim of the club was to undertake conventional challenges, but to either deliberately undermine or to sabotage them en route! He’d stopped half a mile short of John O’Groats having cycled from Lands End (how could he? I know that I wouldn’t be able to). He hitched parts of his walk along the Pennine Way so that he couldn’t subsequently claim that he’d finished it! You’ve got to write an article about it for the Scree website! I replied, and he reluctantly agreed. I imagine that he duly wrote the article, but hasn’t quite got round to putting the stamp on the letter yet!

Yet even though my backpack through the Cairngorms was designed to ‘bag’ the two Corbetts, one of the wonderful things about any walking trip in that part of Scotland is the sense of time which the scale of the landscape creates. I swear that Cairngorm miles are longer than Lochaber ones let alone the really short Lake District equivalents, and carrying a fully-laden backpack including both tent and photography kit, there was no way I was going to get anywhere fast. Undoubtedly I tried at first; the first time someone with a day-sack overtook me I felt distinctly piqued (pun intended)! But with every step I took, the more I found the landscape seeping into me, and slowing me down. For the first time ever on a hike, I lay down in the sun at one point and fell asleep – only to be woken up half an hour or so later by a frog jumping across my breasts! I was also learning that Corbett-bagging has a very different rhythm and mood to climbing the Munros, which it’s hard to rush. Paths are limited, the ground often rough, and the way they’ve been categorized means it’s difficult to combine many hills in one day. There’s nothing particularly glamorous or even exciting about the amount of bog, scree and heather trudging which I already realise will be involved, and in contrast to the stream of people on the summit of Bynack More (reputed to be the easiest Cairngorm Munro), Creag Mhor was empty save the three ptarmigan chicks which I so very nearly stood upon (cue the frantic scuttling of a ptarmigan mother, and me, literally, running for the faraway hills!)

So, is there a different way of peak-bagging, informed by a different kind of a mindset to ticking them off? Or are aimless wandering and peak-bagging polar opposites? Certainly, even while ‘doing’ the Munros (aren’t the verbs we use to describe this process awful), I loved how the challenge took me to new parts of the Scottish Highlands every time, and up supposedly ‘boring’ hills which I wouldn’t otherwise have bothered with. The Corbetts, meanwhile, are even more geographically widespread, and most of their names relatively unknown to most people, including myself. There was something old-fashioned about the experience that I can’t quite put my finger on - indeed, those few people I did bump into looked a little confused, as if to say: what are you doing here? If it is possible to peak-bag in a more wandering, exploratory way, then perhaps the Corbetts are a good place to start…?

This all said, I’m yet to climb another Corbett since. I’ve reined in my workload, and spent two weeks of actual holiday doing practically nothing. I did also spend a good amount of time while staying near Gairloch staring absent-mindedly out to sea, in ways which the above commentary doesn’t capture. Perhaps this time was as important as I know my mountain time is to me. The only memento I brought back from Torridon was a piece of quartzite whose patterns resembled a map, which really got me thinking. Scree-mapping? Before I climb any more Corbetts, my next outing will be a meander mapped from the markings of a piece of Pike o’ Stickle scree in the Langdale Pikes. I just hope the resultant route experiment takes me past a tarn for some more lazy water-watching along the way. I’ll keep watch for breast-loving frogs…

Out-Herdwicking the Herdwick: people-watching on Catsycam

For the last few weekends, I seem to have kept on ending up in the Ullswater valley. I write this as if I woke up on a Saturday morning and lo and behold, there I was transported! Of course, I chose to go, and it’s a good 40 minute drive each way. My point is that, ordinarily as summer visitor numbers to the Lake District begin to increase, I try to avoid hotspots such as Glenridding and the Helvellyn ridges. In contrast, on this occasion, the aim of my upcoming new Catsy-cam experiment was to launch myself into the heart of the busy-ness, and to see how I felt. Of course, there are many reasons to visit the fells, but for me part of it is getting away from it all; being with and in the landscape. My aim with ‘Catsy-cam’? To listen and observe. We associate wildlife spotting with nature, and people spotting with urban environments (cafés, airports, public transport). Yet what if we turned this around? Because let’s face it, the Lake District is actually fairly denuded of wildlife, and with all of us around, no wonder (note to self to wildlife spot next time I visit an airport – I’d best arrive early.)

On my first recce, it hadn’t been long since lockdown had been relaxed, yet already both the sizeable main carpark, and the overflow field which has been opened for the summer, were nearly full. Right enough, I was arriving in the middle of the day when the carparks would be at their busiest having resolutely failed to drag myself out of bed early after a busy week. I grumbled at having to pay £8 to park. It felt wrong somehow – you know, as a local Cumbria resident and all that. Yet, as my two days of recceing would keep reminding me, I was a visitor to these fells as much as anyone. I was adding to the business of the fells and eroding them just as much as any of the other hikers I met along my way. I wasn’t a special case, and I certainly wasn’t in the slightest bit superior; I’d do well to see off any hint of judgement at the col.

To my own amusement, my first recce of ‘Catsy-cam’ was less than fully successful (a form of phrasing I once learnt from a marketing executive as an alternative way of communicating ‘failure’. ‘We don’t have failures here, we simply have less successes!’). Even on a route experiment where the aim was to overtly throw myself in amongst the crowds, I had not only chosen the most esoteric route up Helvellyn’s neighbouring fell, where I was likely to see the fewest people, but having set off so late, both Striding and Swirral Edges were fairly quiet by the time I reached the summit. People-watching? Eaves-dropping? Yes, I did do some. There was the conversation between a young couple who had accidentally set off down Catsycam’s ferociously steep NW ridge. Woman to boyfriend: ‘is that song you’re singing from Frozen?’ Cue: embarrassed silence. Boyfriend, a couple of minutes later: ‘I’ve had it with going down.’ Unfortunately for them, there remained a long way yet to descend, but at least the Frozen discography is a long one! At the summit of Catsycam I met a group of young men checking the football scores. Norwich, Man City, Chelsea. One nil up. How long will it take us to get down? Don’t know. Shall we go now? I’m getting cold. We’re going to miss the Grand National.

On my second recce I’d (slightly smugly) organized to park in the driveway of some friends who live in Glenridding. I hadn’t arrived early as such, but I knew that with a winter of hill fitness in my legs, I’d soon catch up with people on the climb. I met the same litter-picker on the approach path as I had on my last recce, who has obviously been hired by the National Park Authority to keep the trail clear over the course of the summer. We nodded and smiled our recognition. Beyond him, it wasn’t long before I came upon the ‘hordes’ up ahead, making their way up the side of the fells on this, a more familiar ascent route! It was a rare hot day this Spring, and many people were struggling with the effort. ‘Haven’t been to the fells all winter,’ one woman explained to me, as I passed. And of course she hasn’t, what with lockdown. It was a fairly innocuous and brief conversation, but significant for how it pricked the bubble of the experiment I was undertaking; it helped me realise how uncomfortable I was already becoming with eavesdroppping.

I usually love people watching, but in this context it didn’t feel quite right. Certainly, a sense of being unsettled is common to many of the experiments in Scree, since my aim is to challenge existing ways of thinking and being. But of all the experiments so far, I was feeling this most keenly here. I felt uneasy about how it set me apart from others, who (like me) were simply enjoying a day out on the fells. I was on high alert to being judgemental: I found myself laughing at a young man telling his girlfriend that Helvellyn was the second highest point in the UK. Yet what made me so special that I knew this wasn’t true? Indeed, as I entered the glacial cirque of Helvellyn, who was I to scoff at the lines of stick figures making their way along the ridges? Had I not traversed both ridges on numerous occasions myself? It was funny, however, when the same young woman asked her boyfriend what all these stick figures were? Rocks, the lad confidently replied. It must have alarmed them to notice that the rocks were moving. And as for the group of young men walking along playing loud music from a bluetooth speaker, strapped to their rucksacks? I’m saying nothing…

I had partly chosen Catsycam as the locus for this experiment due to its name. Its proximity to Helvellyn not only made it a good place to seek out the crowds, but I was also literally and metaphorically turning my camera upon people, including myself (I watched people posing for selfies along Striding Edge, then took a selfie myself). Red Tarn proved to be a great location from which to do the watching, nestled as it is in the corrie between the two ridges. Yet having sat down on a (stationary) rock by the waterside, it wasn’t long before I started feeling really uneasy. The atmosphere was intense. The glacial landscape creates a natural amphitheatre which was amplifying the sound of voices from all directions, near and far. To take a cliché – I wanted to ‘run for the hills’, yet here I was! It was like the sound of flies around a dead animal. As loud as the dawn chorus, but more frantic somehow. Or maybe it was me who was becoming increasingly frantic! I’m admittedly claustrophobic, especially amongst crowds, but this was the first time I had experienced it in the fells.

I soon moved on from the tarn to the summit of Catsycam itself, whose elevation allowed the voices to have become dispersed. I’d been on the summit, writing, for a good half hour when the search and rescue helicopter arrived to winch a casualty off Striding Edge. I hadn’t noticed Patterdale Mountain Rescue team arrive, but yes, there they were, I thought, packing up my super-telephoto lens and putting it back in my bag... Yet, of course, I wasn’t alone in being a peeping Tom upon the accident. Everyone’s eyes were trained upon the rescue. I’ve read about the science of disaster scenes – why we slow down as we pass a car crash and google what happened afterwards (just as I subsequently googled this rescue later that day). Our fight or flight mechanism is placed on alert, and the events cause us subconsciously to confront our own fears of death, pain, and meaning, from a place of relative safety. Similarly here, with all due respect to the man who had broken his ankle, the scene intensified my own focus upon the broader questions and meanings that this experiment, and Scree more broadly, explore.

While admittedly pushing the metaphor: we are all casualties of our unwillingness to challenge our thinking and behaviour, and prone to continuing as we always have. We laugh at the way sheep follow one another, but don’t we out-herdwick the herdwick? And no. Scree isn’t the mountain rescue team nor the helicopter. Scree isn’t going to rescue anyone, let alone everyone! But perhaps it might encourage us to stop a moment and reflect upon the meaning and consequences of our own actions, as the rescue did for everyone who observed it that day. I made my way down off the fell slightly more slowly than I might have otherwise. I was yet to know the nature of the accident by that point. But in retrospect: my ankles are my weak-spot, and with 22kg of photography equipment on my back…?

Eye-phone

(c) Sputniktilt

First birthday. First step. First word. First Christmas. First tooth. First day at nursery…No no. Actually none of that. Far more significant still. The first submission to Scree is in!

During last Wednesday’s launch, an audience member asked me how long it had taken to develop each route, and how did I come up with ideas? But my literal answer of 5 or 6 days was only partial. ‘My entire lifetime’ would perhaps have been more accurate, for how Scree brings together so much. Over 40 years of climbing the Lake District fells since the day I stubbornly refused to be carried during an 8 mile hike up Cat Bells, Maiden Moor and High Spy aged three. Almost 40 years since my obsession with photography began, down at the River Derwent in Rosthwaite, with my Grandpa’s old Rolleiflex strung around my neck, by which point I was already an avid reader and writer; at about the same age I wrote an extended sequence of poems detailing the precise (rhyming) reasons why I disliked every kind of egg. And over 20 years into a varied career path of campaigning, university teaching / research, and arts management, throughout which environmental themes have provided a common thread. (I also once had a night-shift job which involved beating the living daylights out of broccoli, but that’s another story.) Right enough, as launch day approached and I started panicking about having everything ready in time, I might not have appreciated anyone suggesting I’d had a lifetime to get it done, as the length of my working weeks grew and grew! And not a sprout of broccoli in sight to take my stress out upon…

To open this blog entry by suggesting that Scree is my baby is of course a dreadful cliché, as is the implication that it’s been a lifetime’s work in the making. Is Scree not meant to be about new responses to the fells, rather than old hackneyed ones? Is this not about challenging the clichéd ways in which we’ve come to enjoy the fells? We tend to think of clichés as referring to words and phrases, but might they not equally refer to our behaviour and actions (including those which Scree aims to question)? With all of the above in mind, I therefore won’t go on to suggest that it’s been a labour of love, nor will I allude to how it felt handing my baby over to others to contribute to its development, once the website had gone live! More seriously, as apprehensive as I was about sharing the project, it’s of crucial importance to me that others are involved, since participation is at the core of everything Scree represents. Otherwise, the project will be limited to what I’ve got to offer; as a university creative writing lecturer I always found that I learnt as much from students as I taught them, and my hope is that this will be equally true here. That the project evolves in directions, and involves ideas, that I’d never previously imagined.

I was therefore thrilled, over the course of the weekend, to start hearing that people had started trying out the experiments. First, on Good Friday, a friend sent me a picture of a farm track which she’d only noticed as a result of playing the dice game suggested in the Keswick-Threlkeld railway path experiment along the Pennine Bridleway close to her West Yorkshire home. Then on Saturday, a local friend in Cockermouth sent me pics (see more here) of the light reflections he’d noticed in his partner’s (and also his dog’s?) eyes while running up Melbreak, inspired by the ideas behind the Through the Lake Glass experiment. What interested me about Claire’s pic was how one experiment about the scarring of landscapes (Scars: The Coledale Fells) had influenced what she noticed during an entirely different experiment. And right enough, there’s something equally compelling about the curve of the farm track she photographed as there is with that path on Sail (I’m still working on her allowing me to upload some pics!) Great to also see that the experiments really were proving applicable far beyond the boundaries of the Lake District. Meanwhile, Jo had applied my idea of seeking out reflections in bodies of water to the reflective surface of eyes in ways that I’d never have imagined. ‘Light both ways’ is how he describes it, capturing precisely that reciprocal sense of how we both bring qualities to, and take qualities from, the world in which we live. It’s also an interesting twist on my own experiment. If Through the Lake Glass invites us to seek out reflections, as images of the alternative possibilities which the world might become, then Jo’s take on it turns this around and places the focus upon us. Who are we, and who might we alternatively become? I’m sure it’s no coincidence that Jo is currently exploring another possible version of himself having enrolled on a boat-building course in Portsmouth following early retirement from his career as a GP!

On Easter Monday, I headed out on a favourite route up the nose of Grasmoor. My aim over Easter had been to take time out from Scree, since it’s been all-consuming these past months. Of course, this was always going to be an unrealistic aim, since Scree is composed of so much of who I am and how I think. While hiking in the Moffat Hills in South West Scotland with my Dad, with whom I've been in a Covid bubble, I couldn’t help but wonder how crowded the Lake District was now that the ‘stay at home’ order has been lifted. On our own walk up Hart Fell, we only met one family group of four. And once again, on my run around the fells above Lanthwaite Green, the view of Melbreak across the other side of Crummock Water caused me to pause and reflect upon Jo’s photographs. Scree is partly meant to be about slowing down, noticing things more, and enjoying the process rather than obsessing about the ends. Yet even the intensity with which I’d gone about the project during the first three months of this year in order to meet my launch deadline stood in stark contrast to these principles. How to change this? Who did I want to make of myself in participation with this landscape which I love (and live) so much?

Fortunately the coldness of the wind prevented my soul-searching from becoming all-consuming its own right, or else I’d likely have turned into a self-absorbed ice sculpture scratching my chin, what with this recent cold turn. I continued on to Hopegill Head, one of my favourite fells, not least because it’s the only one I can actually see from the bedroom window of my house in Cockermouth. From the summit, ridges head in all directions, which felt symbolic somehow. I hadn’t brought either of my good cameras with me - this being a day off after all - but my smartphone clearly hadn’t been copied in on the memo. There’s something about taking a photo of the view from the perspective of the view. How does the clichéd saying go? Out with the old. In with the…? I chose the ridge to Whiteside because…honestly? Well. Because it was in the direction of my parked van. And as darkness approached, that seemed like the most sensible decision of all.

All the best laid plans - Not Quite Scafell Pike

Maybe the main thing that’s wrong with things going to plan, is things going to plan. It’s like writing true stories. You know what happens, so what’s the fun in repeating getting there? I’ve been trying to write a book about a year I spent potato farming in Spain for over 20 years now, and all I’ve got to show for it so far are a few aborted first chapters which trusted writing friends have told me aren’t very good, and a keener sense that I write in order to find things out, rather than setting down things I’ve already decided on or done. This is all very well, but if things aren’t going to go to plan, then perhaps they might do so earlier on in a day out hiking than 10 miles and 5,500 feet in, with a 22kg rucksack full of photography kit on your back.

I’ve made Scree available in draft form for a range of reasons. This partly relates to what I say above – perhaps the project is going to be most interesting in its process of development? Means not ends. Messiness as a virtue. It also relates to my enthusiasm about involving others. Yet it does mean that not everything will be perfect in its initial stages. Take the route outlined in the GPX file for Not Quite Scafell Pike. The first time I did the route, I was running – literally and metaphorically. Squeezing it in on a winter’s afternoon after an early start and a full morning of work on other things. And as I acknowledge on the route page, the GPX file I created that day isn’t perfect. I briefly lose the path on my way around Kirk Fell, involving a short dog-leg to get back en-route, and the same again on the way up Piers Gill. Just where the route becomes scrambly, the GPX file leads you left up the rocks onto a faint trod, whereas the main path heads right, across the top lip of the rocks, above the gill. Neither of the above are serious issues. Both alternative routes are entirely safe, and I’m certainly not the first person to have followed the faint trods on the ground. Yet I did feel that I needed to go back and make good, so when a sunny day coincided with the possibility of a day away from the desk…

I got to Wasdale only just early enough to catch the reflections in the glassy surface of the lake. Twenty minutes more of pressing snooze on my alarm clock that morning and I’d have missed them. Yet the reflections weren’t the only thing that caught my attention. Behind me, the road was surprisingly busy considering lockdown remained in force, with cars making their (rather rapid) way up the valley. In the absence of clear guidance, my own interpretation of local during the winter lockdown had been to stick to the northern half of the Lakes closest to my home. Of course, as a freelance artist, the project is also my job, so developing the guidebook is work. Yet I doubted very much that all of the cars rushing up the valley were from hereabouts, and when I reached the village green in Wasdale, turned out I’d been right. Rumour had it that the 12 lads who had just turned up in three shared cars with backpacking rucksacks were from Liverpool. I struggled with myself a bit as I set off. I didn’t want to judge – hate judging – but having struggled all winter with obeying the rules during a solo lockdown, I knew that I was. It was 10am and they were drinking beer already.

There’s nothing like the unrelenting climb up the Scree to Dore Head to take your mind off judgementalism. Nor the mist sweeping in, making the sudden views as it swept clear again even more breathtaking. My aim with most of the routes in Scree is to include options which are accessible, and of all those routes of which this is not the case, Not Quite Scafell Pike is the most extreme. As a competitive fellrunner, who has completed many of the Lakeland classics, I’m no stranger to long tough challenges. But the new route, which my collaging of the Scafell Pike route instructions had created, is a beast (I plan in fact to re-do it sometime soon to provide a more realistic alternative). It’s not hugely long, as such. 12.5 miles. But many of the paths are faint, the going often rough, and the route never stops going up and down the 6,500 feet of climbing involved. Today I’d decided to walk in order to bring my DSLR with me to capture some better photos than last time. I’d been enjoying the fact that carrying my camera had slowed me down these last couple of months. All 22kg of it.

I guess one way of thinking about my route that day was that I was seeking to perfect my route. And of course, there’s nothing like seeking out perfection to ensure errors. First, I cut off the corner at Scoat Fell a little early after the descent from Red Pike: when I checked the red line which my footsteps had just created on the online map, it performed an entire 360 degree loop before getting back en route. I then made exactly the same mistake as last time on my way around Kirk Fell, and the improvement on my line at Beck Head was definitely not a better improvement. This said, most important of all to me was nailing the route up Piers Gill. It was with a certain smugness (hate smugness) that I worked out where I’d gone slightly wrong last time, and took the right line up the rocks. The view, meanwhile, over Styhead towards Blencathra was spectacular; having taken a few pictures with my DSLR, I decided to replicate this on my phone for social media. The photo I took might have been a beauty, but that was soon beside the point as my phone crashed. It was so crashed that I struggled even to turn it off, and by the time I had restarted it…the route was blank. Deleted. Gone. I’d just gone and climbed 5,500 feet with a rucksack which was almost half my body weight for nothing. I jabbed furiously at the buttons on my phone, a bit like how my Dad (who is rather new to the world of mobile phones) is prone to doing. But the technique worked no better for me than it ever did for him.

I sat down on the rocks for a few moments and took a breather. It wasn’t far now until I reached the Corridor Route, let alone Lingmell Col. I was almost there - as close to the summit of Scafell Pike as it would get, without getting there. Most of the distance had been covered, and almost all the climbing done. But the day out had been wasted. I’d done it all for nothing. I’d failed? Of course I had. It was one of the best failures I’d had for many weeks now. It was one of the best days out - yes, ever, in a flexible sense of ‘ever’. I decided to vary the route down from the way the route would have taken me. Because now I could. And do you know, I think it was an improvement too.

Chocolate orange drizzle cake

It’s my fifth birthday, and Mum has just ruined everything. It’s a hot sunny day in early May, and we’ve been to visit a cottage in Rosthwaite, Borrowdale, which my parents hope to buy with the compensation money from the car-crash. We’re all here – my parents, my two older sisters – spread out around a tartan picnic rug beneath the Bowderstone. And Mum has just cut me a slice of the offending cake. ‘Chocolate orange!’ she proudly announces, holding out a sizeable wedge wrapped in floral kitchen roll, apparently unaware that it’s impossible to improve upon straight chocolate. She has already mentioned three times how difficult the recipe was.

It’s only been 15 months since the accident which had left her with multiple broken bones, and blind in one eye as a result of the impact of the crash causing the bonnet of the car to travel through the windscreen, and into her head. ‘There’s a child in the back,’ she’d said before slipping into a coma. She was referring to 3-year-old me, who had been wrapped up in a tartan rug along the back seat, which come to think of it rather resembled the one we were currently sitting on, and who was now trapped in the rear footwell where the force of the crash had thrown me.

‘If she’d been sitting up, she’d have gone straight through the windscreen,’ I’d heard my parents say to their friends. Those were the days before seatbelts ‘in the back’, and I was left under no illusion how lucky I’d been to escape uninjured apart from a few bruises, and a lifelong fear of the loneliness, unapproachable whiteness and what at the time felt like the hugeness of hospital beds.

Back in the moment, I try to smile, hoping that Mum will think that my eyes are watering from happiness. ‘Thanks Mum,’ I say. ‘It’s yum.’ In fact, I didn’t tell Mum the truth of my disappointment about the cake that day until two years ago, a year before she died.

Not that these events did anything to dent what became a 40-year (and ongoing) love affair with the Lake District fells, which commenced later that day with a first ascent (by me) of Castle Crag. By aged 16 I’d climbed all the Wainwrights with my Dad, which we celebrated with a can of Fanta each on the summit of Lank Rigg in Ennerdale (my, how my parents knew how to celebrate…) Since that day at the Bowderstone, we’d spent every October half-term holiday at the cottage, plus every other winter weekend until Easter when holiday bookings would start coming in. Many criticisms are rightly levelled at second-home owners, and their impact upon local Lake District communities . Yet back then, Borrowdale didn’t feel like a second home to me. Emotionally, it was my first home, even when I’d become a teenager and most of my peers were occupied with very different things. Being in the hills both then, and now, was when I felt most ‘at one’ with the world; I can still taste the betrayal upon hearing that my parents had sold-up the cottage without telling me, when I was in my mid-twenties. So, when I saw the opportunity to go and work and live in the Lake District through a Creative Writing lecturing job at the University of Cumbria a couple of years back now – well, of course, I leapt at the chance.

So what does this have to do with Scree? Perhaps everything…for doesn’t the story involve elements of everything that Scree seeks to challenge? And that’s my point in telling it. To say yes, I’m implicated in everything that Scree questions – have been since an early age, and continue to be. My parents were only able to purchase the cottage through the car-crash compensation monies, and I’m fairly certain that as a child I worked through my own trauma in the fells, whether consciously or not (the crash is my first memory). As I grew up, peak-bagging became an obsession. First the Wainwrights. More recently compleating the Munros. Then in my mid-thirties I took up fellrunning, and began pitting myself against the fells in yet another competitive form. Perhaps the exception is the notion of being separate from ‘nature’ - an idea which would have made as little sense to a young version of me as it does now. In contrast, I’ve always felt an innate connection to the fells – a sense of one-ness which I experience most keenly when running as fast possible downhill and the boundary between me and the hill dissipates. Indeed, when my Mum died very suddenly last year of cancer, during the first Covid lockdown, where did I most want to be, and what did I wish to be doing? In the Lake District fells of course, running out my grief as fast as I possibly could.

‘I’m going to do this,’ I said to her, as I lay my head on her pillow the night before she died, referring to the ideas I’d been mulling over for some time, which have become Scree. ‘I’m going to be ok, and I’m going to make this happen.’

One of the key early experiments in Scree sets out deliberately to explore the process of writing grief upon mountains, by running up and down one of the worst scars of a path in the Lake District Fells, on Sail, in the Coledale fells above Braithwaite. That morning, setting out up the path towards Force Crag Mine from Braithwaite, I was beset by doubts about what I was doing. Wasn’t I about to do precisely that thing I’ve come to criticise? What was the point of that? Yet if I’ve learnt anything during my years as a writer and artist (and academic), it’s not to resist instinct. Since these were experiments after all, perhaps I’d find out what it meant in retrospect, in the process of doing?

When I reached the bottom of the path between Scar Crags and Sail that morning, there was a fresh layer of snow covering all previous tracks, as if here it actually was – my chance to rewrite everything differently. And the more I ran up and down the zig zags of that path, the more I realized that I really was doing things differently. This wasn’t a writing of my grief upon the mountain, it was becoming a sharing of my experience of it, with it. I felt more aware than I ever had of what I was bringing to and taking from the fells, and left that day feeling a sense of connection like I’d never experienced before. Acute. Attentive. And I suddenly found myself able to write about my grief following Mum’s loss in a way that I hadn’t been able to previously.

I guess that’s what this project is about. These little shifts in thinking. Little changes. Maybe leading to bigger shifts. Maybe even fundamental change. Who knows? But by then I was really hungry, since I’d forgotten to eat all day. If only for some chocolate orange drizzle cake…

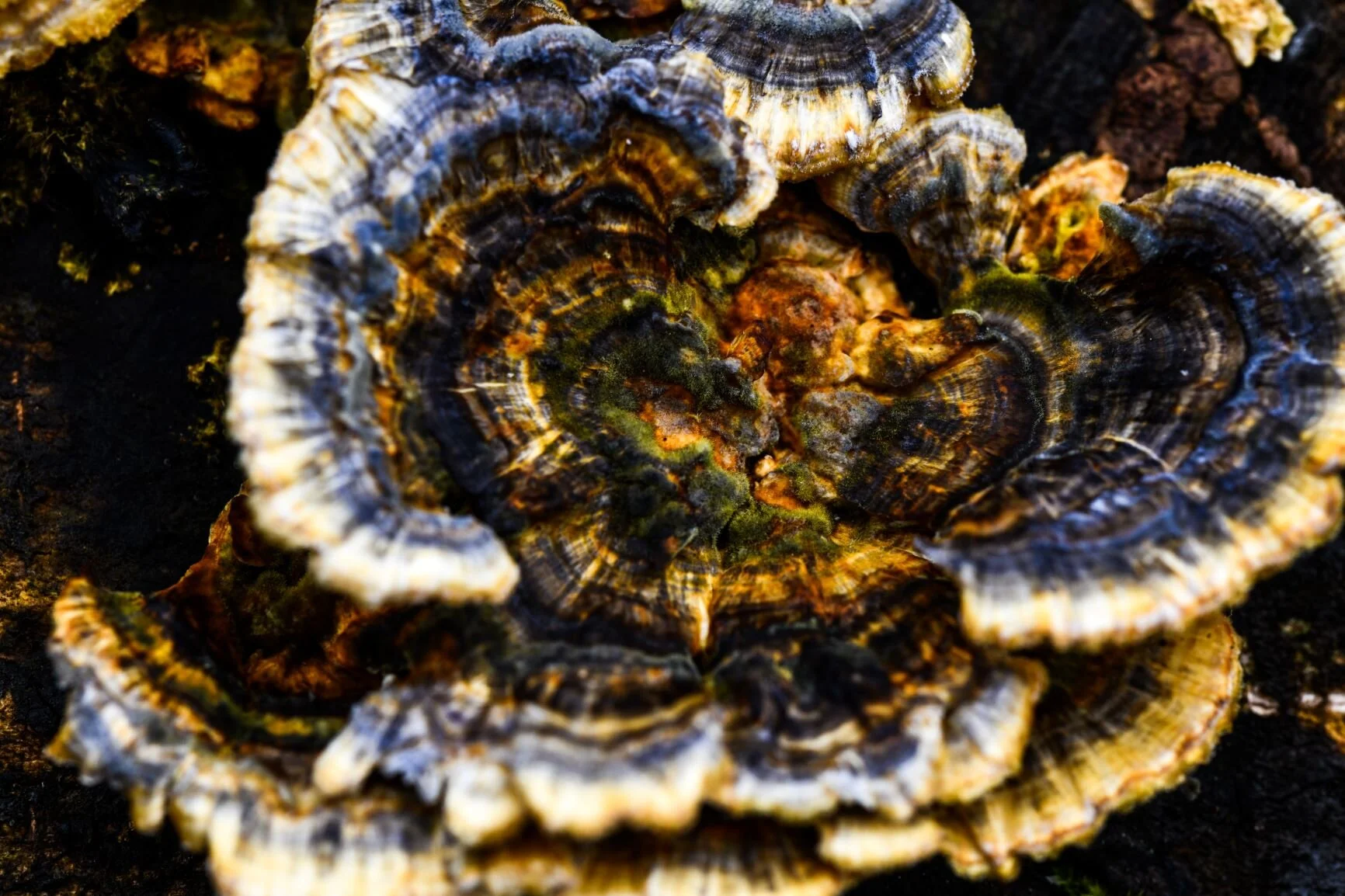

PS the below fungus are from a recent visit to the Bowderstone. Now that’s proper growth. I couldn’t help but share them here.

Binsey: because everything starts somewhere

Recce #1

It fits. My first recce of a route for Scree was accidental. In fact, it wasn’t what I’d hoped to do in the slightest. The idea had been to run a loop in the hills behind Skiddaw en route to visit my Dad, with whom I’ve been in a Covid bubble, for Christmas. Longlands Fell. Great Sca Fell – the ironically named, rather smaller (less exciting?) foil to its local namesakes. Meal Fell. Great Cockup (yes, really). Hardly the Lakeland fells that one might immediately identify for a grand day out. But wonderful running country nonetheless, and a great place to escape what I anticipated might be the Christmas Eve crowds. If only I’d anticipated the road conditions. I’d been so busy renovating my house that I hadn’t quite realised how cold it had been, so the sheet ice on the 20% gradient road towards the start of the route took me entirely by surprise. Not a great surprise, either, since the only way out of there was a half mile reverse along narrow roads in my VW Transporter van, with a dodgy wing mirror (note to self…)

I’d been running late as it was, and by the time I finally reached a road junction and was able to turn around, my options were running out. Well, apart from Binsey that was - and there she was, sitting proud and stout straight ahead. I’d planned to make a start on Scree in the New Year, but I’d already had the idea of my looped route which has become Loopy Binsey for a few months now. And frankly she was the only fell that I had any chance of exploring in the time left available. Binsey. A small round pudding bowl, with two routes up and down which cut almost straight lines from road to summit. How was I going to satisfy my need for a good long run on that? Binsey. As Alfred Wainwright put it: ‘Binsey is the odd man out. This gentle hill rises beyond the circular perimeter of the Norhern Fells, detached and solitary, like a dunce set apart from the class…[her] outline is too smooth and gently graded to attract much attention, and its ascent from most directions is an easy trudge lacking in excitement.’

Yet wasn’t this exactly why I’d chosen her for my initial experiment? My aim? To walk around Binsey as many times as possible, while travelling uphill at all times, without reaching the summit. Why? To challenge the need for targets (aka summits). The need to go longer and faster, and to climb the biggest hills in the best areas. To find out if it were even possible? I’d established on the OS map that my route was legally allowable in terms of access laws, but would land management practices such as walls and fences come in my way?

I left my van at the parking spot just off the road to Uldale, and set off instinctively clockwise. A small trod took a diagonal line across to the corner of a wall, before contouring more gradually around the fell. At first I followed this, glad to be on a small path rather than bashing through bracken and heather. But soon the path began to contour downhill, requiring me to continue through the undergrowth. In fact, it didn’t take long before I started obsessing about whether or not I was going uphill. Over-compensating. Losing sense of what was uphill and what was down. And then berating myself for failing when the crags at the west end of Binsey caused me to take a few steps down! I had barely been going for twenty minutes, and my recce was already broken! I stopped. Began to laugh. Was I genuinely worrying about this? I took a moment to look around. To Skiddaw behind. To Bassenthwaite Lake, and the Coledale and Newlands fells beyond. Then continued. As I neared the summit I noticed a couple enjoying the view, and decided against performing a few final micro-loops around both the cairn and them for the sake of appearances, and made straight for the highest point.

One loop. That was it. I’d managed one paltry loop, when I’d hoped for at least three or four. What if someone else did the route and beat me? I sighed, looked at the view for a while, then ran back downhill at speed. Lockdown Christmas was calling.

Recce #2

Who knew? Boulder, St Anton, Binsey? Less than a fortnight later, I was back at Binsey, and in the meantime it had turned into a snowboarding resort! The main path had turned into a piste, and there must have been at least two dozen boarders enjoying the snow.

With decided self-consciousness, I set off on this occasion anti-clockwise, literally off-piste. The heather was knee deep, and laden with a good few inches of snow, making the going slow. Unsurprisingly, no one had come this way before me, and it didn’t take long for me to wish that I hadn’t either. It was a stunning day. Ferociously cold, with a strong breeze and no lack of clouds, but also sunny, with an incredible low winter light. If only I weren’t walking away from this, towards the dark side of the fell. If only I were in those fells, over there, I thought, looking over to the Skiddaw range. Wouldn’t that be far more fun? Of course, the hill over there is always sunnier.

Despite views beginning to open up across the Solway to Scotland, my mood dipped markedly as I trudged through the deep snow in the shade of Binsey’s northern flank. My entire route to the summit, even by this circuitous route, was unlikely to exceed two miles, but it felt relentless. Pointless. But wasn’t that the point? I thought, looking up for a moment. Ahead, a barn owl hovered low above the snow and bracken. I looked down. The bracken and grasses at my feet themselves had written messages in the snow, inviting deciphering. The wind blew the snow from my tread, and then filled it back in behind me, inviting me to keep going.

The sun set as I reached the summit, after another single circumnavigation. As it dipped below the horizon, the temperature dropped even further, and suddenly. I thrust my hands deep into my pockets and watched the snow being bleached all shades of pink and orange, until the cold became unbearable. Despite the weight of my sack and all my photography equipment, I ran back down the hill again to the van, whose locks had frozen solid. So now what? All the snowboarders had already gone home for the day, and all that was left was me, the cold, and my quickly fading sense of initiative.